Cultural Heritage

Saga of Hofstaðir: Unearthing the Past in North Iceland

At Hofstaðir in the district of Lake Mývatn, north Iceland, extensive archaeological excavations have been carried out over the past three decades. The site includes remains from the Viking Age to the 20th century. A huge Viking-Age structure was excavated: a hall or longhouse where people gathered on social occasions, with other smaller buildings around it. The hall is one of the largest structures ever excavated in Iceland. In addition, a churchyard was excavated at Hofstaðir, which is one of the oldest churchyards unearthed in Iceland. Whole families were laid to rest in the cemetery, and their bones yield evidence about their lives. The face of one of the women buried at Hofstaðir has been reconstructed using DNA technology, and a drawing of her is included in the exhibition.

Hundreds of people have been involved in the archaeological project at Hofstaðir and elsewhere in the vicinity of Lake Mývatn. The project has resulted in more than 100 books, academic papers, reports and student essays. The objective of the webpage is to provide insight into the complex process of archaeological research. During the many years of the Hofstaðir project, technological advance has been rapid in all specialist fields of archaeology. The Hofstaðir project has made an important contribution to the development of an extensive network of scholars carrying out a wide range of research in the north Atlantic region. A long-term study such as the Hofstaðir project clearly exemplifies how ideas, knowledge and interpretation of the past change over time. The

exhibition explores the archaeological finds at Hofstaðir, archaeologica research, and the ways that different scholarly disciplines seek answers to questions about:

● Why has more extensive research been carried out at Hofstaðir than

elsewhere?

● What research questions have been answered?

● Are there lessons to be learnt from the life struggles of past

generations?

Unknown

Latrine

Kitchen/Storeroom

Corridor

Corridor

Hall

Living Quarters

Kitchen/Storeroom

Smitty

Smitty

Storeroom

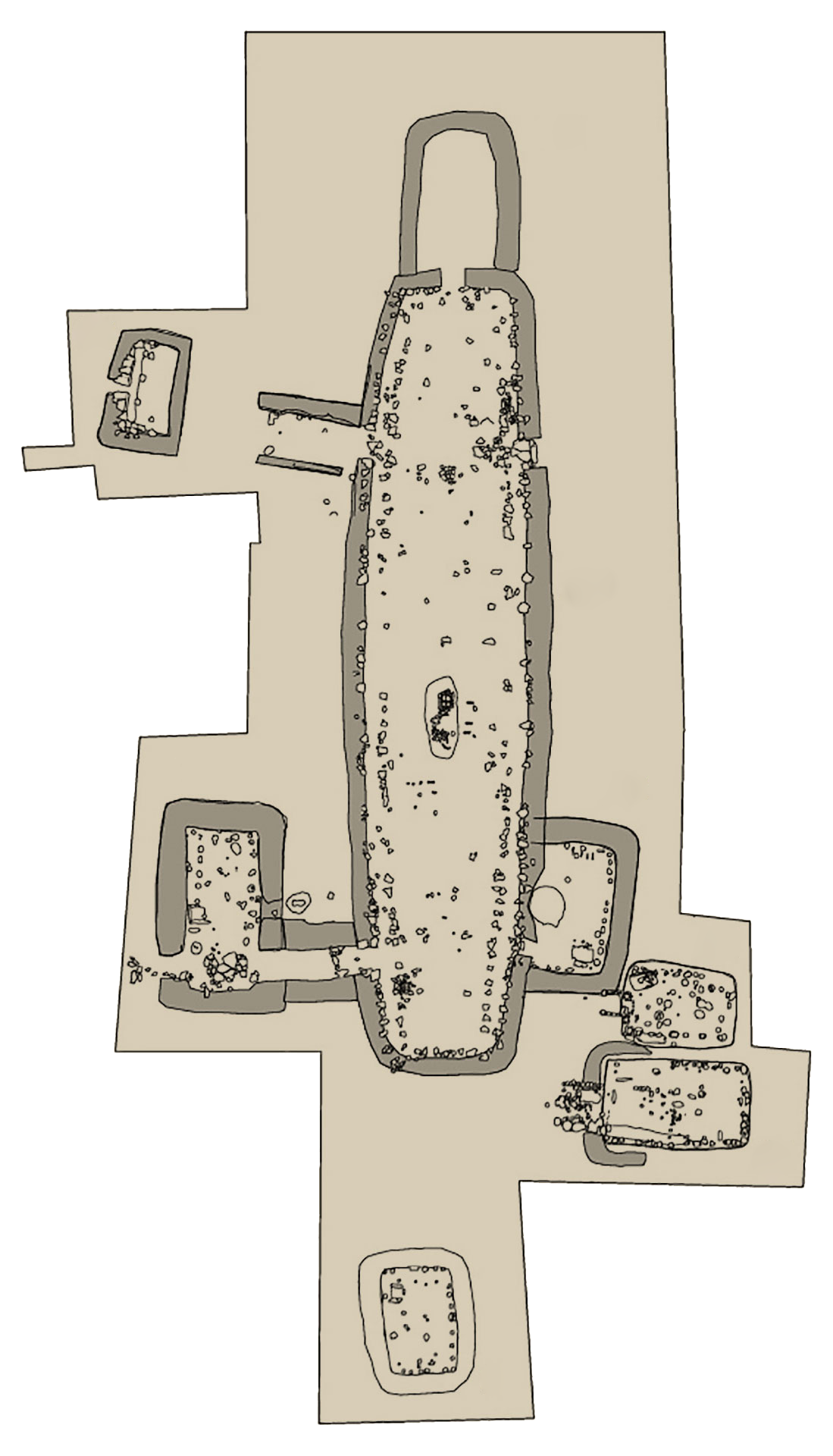

Above: The Viking Age feasting hall at Hofstaðir. Hover over the image to learn more about each building.

© The Institute of Archaeology, Iceland

Utalization

Medieval walls

In many regions of Iceland medieval field walls survive. Built mostly of turf, they may have been as tall as a man when originally built. They probably served various purposes relating to land use, management of grazing, and demarcation of property. Dating of these old walls, by reference to tephra layers of known date, demonstrates that many of them were built in the 10 th and 11 centuries. One such wall lies a little to the east of the Hofstaðir homefield. In the Þingeyjarsýsla region, the total length of these huge structures is about 700 km. The Grágás law code, which dates from the mid-13 th century, makes provision for how such walls were to be built:

“If a man is requested to build a wall…. they shall build a legal wall. A legal wall is five feet thick down at ground level and three at the top. From the base it should come up to the shoulder of a man whose arm size gives valid ells and fathoms.”

(Translation Andrew Dennis, Peter Foote, Richard Perkins: Laws of Early Iceland II)

Homefield

Around the three farmstead sites was a field wall to safeguard the homefield from encroachment by livestock. From the very beginning of the Settlement Era it was customary to enhance grass growth by spreading food waste, ash and dung on the field as fertilisers. Such improvements at Hofstaðir were explored using micromorphology techniques. Soil samples are taken and thinly sliced for examination under the microscope. This reveals the proportion of charcoal fragments, seeds and other substances in the soil; alterations in the proportions indicate what fertilisers have been spread on the grassy homefield, and in what quantities. It transpired that the Hofstaðir homefields were not particularly good for cultivation. Hence it cannot have been the quality of Hofstaðir as farmland that led to its development. The homefields were, however, well maintained from the early days until 1477, when such soil improvements went into decline.

Seeds

In the homefield at Hofstaðir, furrows made by an ard (a simple plough) are visible. These are evidence of cultivation, as the ard was commonly used to plough cultivated land. Barley is frequently found on Iceland’s oldest archaeological sites, and the early settlers probably tried growing the crop in Iceland, though grain was also imported. Barley is the hardiest cereal

crop, and the most likely to thrive in such a northerly location. Only a small quantity of barley was found in the floor of the feasting hall at Hofstaðir: just 23 seeds. The paucity of the find may have various reasons.

Perhaps barley was a luxury commodity in this region? Or perhaps it was a function of poor conditions in the hall floor for conservation of organic materials, or of disturbance of the site in excavations in the early 20 th century? Analysis of the seeds indicates that they came from elsewhere, in Iceland or abroad.

One oat seed was found, but it is believed to have been a chance addition to a sack of barley. Seed research indicates that crowberries and chickweed were probably used for human consumption at Hofstaðir; crowberry seeds were especially abundant in the privy!

Pollen

Tiny pollen particles are carried by the wind. Study of pollens in sedimentary layers in Helluvað Pond, formerly a wooded area, throws light on utilisation of woodland in the Lake Mývatn district. From the Settlement Era until 1300 the number of birch trees shows a marked decline, followed by a period of greater stability; but by then the woods were considerably smaller than they had been before the settlement. The inference is that during the early centuries the woods were over-utilised or burned in order to provide more land for cultivation. The environmental changes that took place in the Lake Mývatn district may not all have been anthropogenic (caused by humans), as the climate also changed in that period. At the time of the settlement around 900 AD Iceland was experiencing a warm period, which was followed by a cold period commencing in the 14 th century, known as the Little Ice Age, that had an impact on vegetation all over the country.

Woodland was never abundant at Hofstaðir itself, and it was quite severely affected prior to a volcanic eruption in 1477, but then made a good recovery and remained largely stable until the 18 th century. Could the feasting hall, with its need for large quantities of timber, have been a factor in the extensive utilisation of nearby woods?

Hofstaðir: a hub

No reference is made to Hofstaðir in saga literature, yet more is known about the life and work of the farm‘s inhabitants than in most places in Iceland, thanks to extensive archaeological research at Hofstaðir and elsewhere in the Lake Mývatn district. No contemporary written documents survive about Hofstaðir in the early centuries of Iceland’s history, so the story is told through archaeology alone. Archaeologists seek answers to their questions about the people, what they did and how they interacted, their impact on their environment, and vice versa.

Three farmhouse sites from the Viking Age are known at Hofstaðir. Indications are that in the 10th century the three farmsteads were inhabited at the same time. This conflicts with received ideas about the early settlers of Iceland, who were believed to have established individual, widely-spaced

farms. The oldest farmstead site is at the north of the cluster, known as í Brekkum. Here a hall/longhouse and other structures were built, after the “Settlement Layer” of tephra was deposited by a volcanic eruption around 871 AD, but before 940. The duration of that phase of habitation is unknown. The site is still largely unstudied. The great feasting hall and the buildings around it were constructed after 940, and by about 1030 they had fallen into disuse. A church and the churchyard also date from the 10 th century, as does a farmstead to the west. Farmhouses at Hofstaðir continued to be built on that site for the next thousand years, and a “farm mound”* was gradually formed.

The prosperity of the owners of Hofstaðir is not manifested in worldly goods, but in the size and diversity of the buildings. The feasting hall is one of the largest Viking-Age structures ever excavated in the Nordic region.

The churchyard is also one of the largest from the early Christian period in Iceland. The church was a lofty building, visible from far away. In the latter half of the 10 th century, at the time of the feasting hall and the church, Hofstaðir must have been an imposing sight. The obvious inference is that the inhabitants of Hofstaðir deliberately set out to build the place up as a hub for the region west of Lake Mývatn. The development at Hofstaðir may have been intended as a challenge to the dominance of the old manors of Reykjahlíð and Skútustaðir by the lake.

*Farm mounds build up over centuries, made up of building materials (turf, rock and timber) together with human and animal waste.

Yfirlitsmynd um fornleifar og rannsóknir á Hofstöðum. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

- How is it best to interpret the relics at Hofstaðir?

- How can archaeology shed light on a rivalry for power in society in the early days of the Old Commonwealth?

- How is the history of the people of Hofstaðir unearthed?

Feasting hall

A feasting hall was first built at Hofstaðir after 940. It was large, about 28 metres long, while the average hall was 12-16 metres in length. At around the same time a sunken pit-house and smithy were built. During the 10 th century the owners of Hofstaðir continued to prosper, and the hall was extended to 38 metres in length. Other structures were built at that time: a small dwelling, a privy, another smithy, and annexes to the feasting hall, including a pantry with a large cask embedded in the floor for storing food in whey. While the size of the hall was unusual, the construction was conventional, with two rows of posts supporting the roof and a sunken middle section, with benches and sleeping spaces on either side. Two postholes contained small stones, a spindle whorl and a knife, which had been deliberately placed there. Could this relate to a ritual during construction? Much of the interior of the hall was panelled, and at either end a space was partitioned off. The central space was the largest, with a long hearth down the middle. There are indications of partitions in the platforms around, probably forming bed-closets. The long hearth was 1.2 metres long; such hearths in halls are generally 1-2 metres long, while longer and shorter examples are also known. A long hearth was situated in the middle of the hall, and research has shown that this was the focus of the house. Floor layers are thickest around the long hearth, and this is where most objects are unearthed. The floors of the Hofstaðir hall yielded diverse objects, most of them for daily use, while a few were rarer items.

Uppgröftur á veisluskála. Mynd tekin frá suðri til norðurs. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

Feasting and religion

The power structure of chieftains in early Iceland relied heavily on social gatherings and feasts. The objective of such events was seen as being to reinforce feudal relationships, and also to attain a position of influence. The Hofstaðir hall was not built until the mid-10th century, by which time the community in the region was quite well-established. Thus the hall is seen as reflecting an attempt to achieve power. At Hofstaðir there are threemajor indications that this was a site for social gatherings: first and foremost the great hall, which could accommodate a large number of guests. Secondly, animal bones indicate an unusually rich diet, with a large proportion of fine meats of bullocks, suckling piglets and lambs. There are also indications of animal sacrifice, which cannot easily be distinguished from pagan religious practices. A total of 23 bull skulls were found, some with horns; these are believed to have been hung on the outside of the hall. Signs are seen of unusual practices in slaughtering the beasts: some of the bulls had been stunned before slaughter by a blow between the eyes; and the occipital bone shows signs of chopping with a blade, indicating that the animals were decapitated while standing, using a sharp sword or axe. This would have been a dramatic sight, as blood would gush from the severed carotid artery.

Deconsecration of the hall

The archaeological finds at Hofstaðir throw light on the adoption of Christianity in Iceland. They indicate that the old pagan religion and Christianity were not seen as incompatible. For a considerable period in the 10 th century and into the 11 th , the two religions coexisted: a hall adorned with the skulls of sacrificial animal offerings, and next to it a lofty church.

Around 1030, thirty years after Christianity was formally adopted as the religion of Iceland, the hall was abandoned and deconsecrated. That process involved a variety of rites: the skulls of sacrificial animals were removed and concealed; the whey-keg in the pantry was filled with slag from iron-smelting, and the ember-box* at the long hearth was removed. A sheep was sacrificed – killed with a blow between the eyes and left inside the building. Usable timbers were removed.

Signs of the old religious practices were deliberately removed and concealed. The time of the old religion had come to an end, and a new one had begun.

Cattle skull excavated. © The Institute of Archaeology, Iceland.

* Embers were placed in a container to keep the fire alive. The fire was reignited in the hearth by blowing on the hot embers.

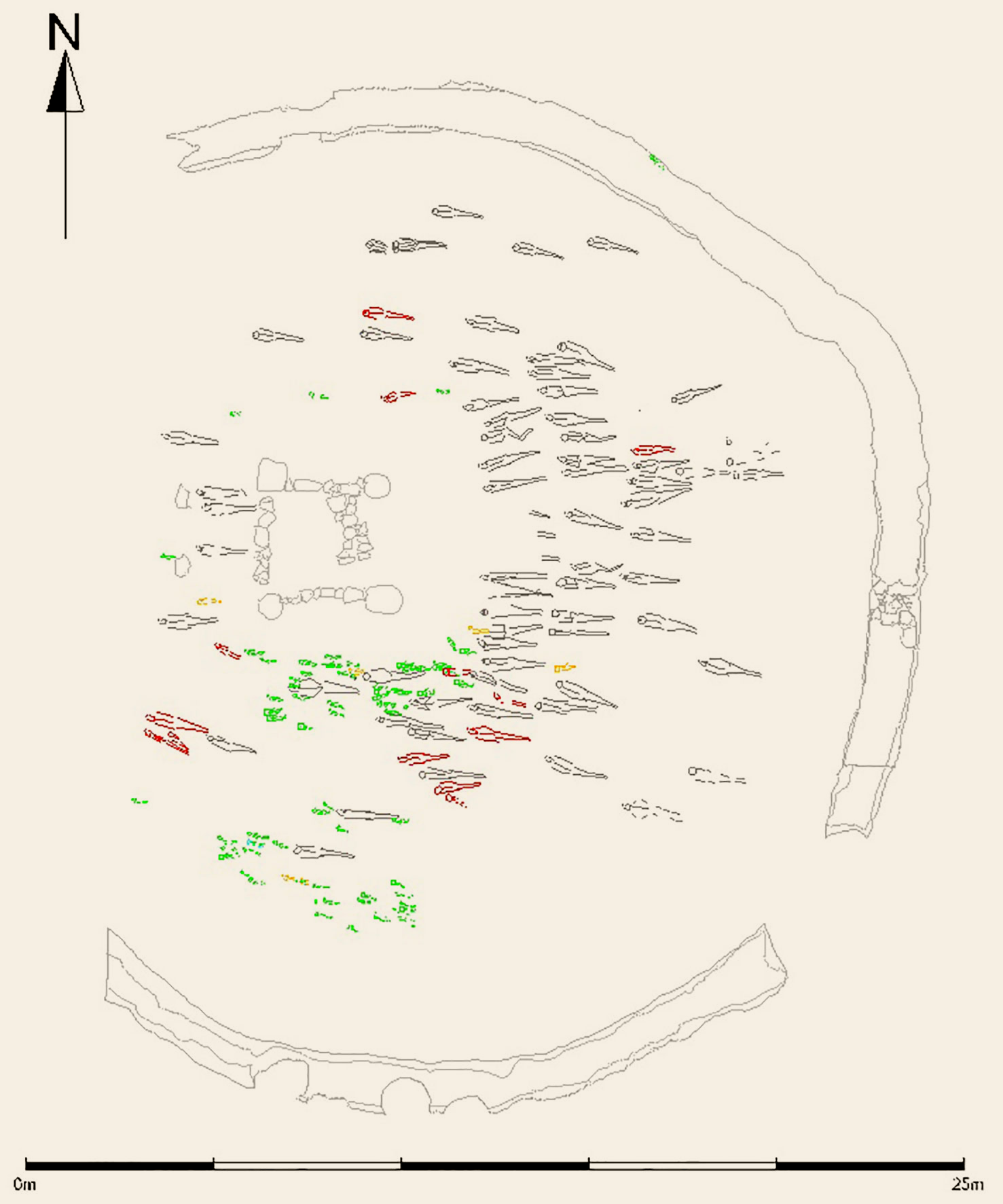

Church and churchyard

The first church at Hofstaðir was built in the latter half of the 10 th century. There may have been a church on the site until the Reformation in the 16 th century, but this remains unknown. Burials in the churchyard commenced in the 10 th century and ceased before 1300. Evidence was found that the church had been rebuilt in the 12 th century. The earlier and later churches at Hofstaðir stood in the middle of the churchyard. Both were wooden stave churches. They were small, the smaller one only 9m 2 in area. The corner posts were large, about 80cm in diameter, which indicates that the churches were on the other hand, very tall. The churchyard was 25m in diameter, enclosed by an octagonal turf wall. In the churchyard were 169 graves, all of which have been excavated. Most of the adults were interred to the east of the church – women mostly at the north and men at the south, as was customary. Children were generally buried at the south wall of the church. In four cases bones had been transferred to the churchyard having first been buried elsewhere.

The cemetery at Hofstaðir; in the photo, children’s graves are marked with color. © The Institute of Archaeology, Iceland.

Daily Life

All archaeological finds, from the most splendid treasures to simple utensils, throw light on the life of past generations, and reflect resourcefulness, creativity, adaptability, artistry, access to resources, commerce and connections.

Excavation of the Hofstaðir feasting hall and adjacent buildings unearthed about 1,200 objects from the 10 th and 11 th centuries, of diverse kinds. The largest categories of finds are metal and stone. Preservation of organic objects is generally poor, and few leather, wooden or textile objects were unearthed. Bones, however, are well preserved.

● Do the archaeological finds at Hofstaðir reflect the unusual nature of the site?

Origins

Most of the objects were found in middens – refuse dumps containing layers of ash from hearths, food waste and other rubbish. Floors were regularly swept to keep them clean, and the waste went into the midden. This is one reason why undamaged objects are found in middens: they

have been dropped and trodden into the earth floor, then later swept out with the rubbish.

Objects from Hofstaðir comprise two rough categories, which overlap. In the older occupation layers are objects that relate to the Settlement Era, around 900 AD. The early settlers of Iceland had brought possessions with them from home or acquired them during the time when travel between Iceland and mainland Scandinavia was frequent. Imported objects are common, such as cooking pots and spindle whorls of Norwegian soapstone*, a grindstone**, whetstones, combs, flints for striking sparks, and beads of glass and amber. Metals such as silver, copper and lead also had to be imported. It is probable that some of the iron objects in the oldest occupation layers were imported, as iron tools were necessary for woodworking, repairs and agriculture. It is difficult to distinguish between imported and home-smelted iron, but smithies, slag and cinders indicate

that bog-iron was smelted at Hofstaðir.

In the later occupation layers, more Icelandic materials are seen. People learned how to live in their new surroundings. Basalt rock was used to make simple oil lamps and scale weights, sandstone for spindle whorls, and beads were made of jasper and quartz. Many colourful stones from elsewhere in the country have also been found, such as quartz, scolecite and Iceland spar.

Signs of iron smelting and metalworking are also clear. Large quantities of slag were found, and in the floor a stone mould was unearthed in which iron ingots were cast. Ingots were then used to make small iron objects such as nails.

* Soapstone is a soft, carvable rock which is not found in Iceland. It occurs in Shetland and Greenland as well as Norway. The form of the soapstone cooking pots found in Iceland indicates that they originated in Norway.

**A grindstone is a circular stone used for sharpening blades, rotated manually or by a treadle.

Everyday and special occasions

Just as the quantity of everyday objects can provide a clue to unusual activity, so a single rare object can do the same. One of the objects unearthed at Hofstaðir is unique: a silver pendant found in the hall floor. One side is incised with a simple but ambiguous image: it may be the hammer of the Norse god Þór, a cross, or a face. Other valuable items had been trodden into the hall floor and lost, perhaps during feasts. These include glass, amber and stone beads, a copper-alloy pendant, silver wire, and a ring-headed copper pin. Fine pins of bone were found in the midden, with broken shanks but undamaged heads. Were they thrown away when they broke, with no attempt to repair them? Or were they lost on the hall floor, and later swept out with the refuse?

The vast majority of the finds are everyday objects, reflecting life and work on the farm. Spindle whorls and stone weights from warp-weighted looms are the only remaining evidence of the vast amount of work involved in processing wool into clothes: plucking the sheep’s fleece, then washing the wool, carding, spinning and finally weaving. The wool provided all the textiles required for the home. Spindle whorls were found in the floor layers of the hall and the pit house. The very few textile fragments unearthed are all of wool vaðmál (homespun cloth). Also in the pit house ten stone loom-weights were found, indicating the location of a warp-weighted loom.

Extensive evidence of ironworking was found, and it is clear that the residents of Hofstaðir had easy access to bog iron and fuel such as peat, turf and wood for smelting. The iron was smelted and worked in the smithy. Every farm had its own smithy, where tools could be made and repaired.

Subsistence

It is evident from the objects found at Hofstaðir that their owners strove to make them last. They are worn out from intensive use, and signs of repairs and repurposing are seen. Soapstone from a broken cooking pot might be used to make spindle whorls. Cinders and slag in the hall indicate that minor repairs were carried out there. Crucibles are found containing traces of metals melted in them for fine metalwork. Probably silver or copper objects were generally melted down to make new ones, or for repairs. The objects unearthed give no indication that the owners of Hofstaðir had more access than other local residents to imported commodities. Despite the large buildings and the strong social network, subsistence was key. The utilisation of Icelandic resources, or access to them, was a necessity for the chieftains at Hofstaðir, as for others.

Food and diet

Diet

Clues to diet can be read from food waste such as animal bones and eggshells found in the middens. Hearths, cooking pits and vessels provide insight into how food was prepared. Study of human bones also contributes vital information. In some cases, signs of malnutrition are seen. In addition, isotope analysis is carried out on human and animal bones in order to explore diet.

● What did people eat at Hofstaðir, and what clue does that provide to

their social status?

● How did diet influence the health of the Hofstaðir people?

Middens

Middens, containing waste discarded by humans, are a source of varied information about people’s lives. Middens are generally located near homes but separate from them. Ash from the hearth, food waste and objects that no longer served their purpose were discarded there. Research on middens throws light on the history of the place, what people ate, and how diet evolved.

Animal bones

A variety of animal bones were unearthed at Hofstaðir, reflecting the rich food resources of the Lake Mývatn district. The diet included mutton, beef, horsemeat, pork, birds and their eggs, freshwater and saltwater fish species, and marine mammals. In addition, bones of cats and dogs have been found, as well as seashells, which probably arrived with seaweed, used for fuel or fodder.

The animal bones at Hofstaðir show that during the Viking Age the residents ate a diet essentially similar to their neighbours: local waterfowl and their eggs were used, and sheep were kept for their wool and cattle for milk, while their meat was also eaten. But there are indications that consumption at Hofstaðir sometimes differed from that on other farms. Much more saltwater fish and seabirds were eaten, and there is evidence of the slaughtering of bullocks, lambs and suckling piglets, presumably in order to cater for the feasts. After the 12th century little evidence of diet at Hofstaðir is found based on animal bones, but a small waste heap was found by the churchyard, dating from about 1300.

This contains a far higher proportion of marine mammal bones than the older accumulations – especially harp seal. Two different interpretations are suggested by experts: this could be a sign of shortage, i.e. that it was necessary to go farther afield to find food. The bones have been broken open to make use of the marrow, indicating that every part of the seal was used. Alternatively, the presence of harp seals off Iceland may be viewed in a broader context: the seal population may have increased, perhaps reflecting changes in its food sources.

Human bones

Malnutrition makes its mark on human bones. Analysis of bones from the Hofstaðir churchyard shows less indication of malnutrition than contemporary bones from other locations. The Hofstaðir bones also display various other signs of good health. Hofstaðir residents were unusually tall and long-lived, indicating that their health and nutrition were above average.

At Hofstaðir and elsewhere in the Lake Mývatn district detailed isotope analysis has been carried out on human and animal bones in order to explore diet. The isotopes enter the body in food, and by analysing them it is possible to study e.g. origin or diet. At Hofstaðir analysis has been carried out on stable isotopes* of carbon (δ 13 C), nitrogen (δ 15 N) and sulphur (δ 34 S). Such research reveals the proportion of foodstuffs consumed from saltwater, freshwater and land sources. The findings show that freshwater food sources (fish, along with waterfowl and eggs) and land-based sources (meat, milk, berries, lichen and other food plants) were predominant.

Saltwater food sources were less important, especially by comparison with bone evidence from coastal regions. Three individuals, however, differ from the rest with regard to diet, and this may be a clue that they had only moved to the Lake Mývatn district in the last decade of their lives.

Isotopes are variants of a particular chemical element in which the number of protons is the same, while the number of neutrons differs, and hence the mass numbers differ. Most elements have one or more natural isotopes, both stable and radioactive.

Skeleton excavated in the cemetery at Hofstaðir. © The Institute of Archaeology, Iceland.

The Family

In general, the oldest Icelandic churchyards are believed to have served only the farm where they were located, and possibly outlying estates. Research on the human bones at Hofstaðir supports that theory. Genetic and health research on bones provide a range of information about the people and their community.

● What people lived at Hofstaðir?

● What kind of life did they live, and what was the relationship between

them?

Family ties in the churchyard

Pathological studies and DNA* analysis have yielded evidence of close familial ties among the people buried in the Hofstaðir churchyard. It transpired that arthritis of the hip was considerably more common at Hofstaðir than elsewhere in Iceland, or in comparable foreign bone assemblages. The causes of arthritis are complex, but research by DeCode Genetics has shown that arthritis is hereditary in Iceland, and several familial lines with a high risk of arthritic hip have been identified. The Hofstaðir findings indicate that the inhabitants of the farmstead were close

relatives; they are also evidence that the hereditary arthritis known in Iceland today dates back to the early centuries of Icelandic history.

DNA was analysed from ten of the Hofstaðir skeletons. The tests revealed that they included a mother and her son and daughter. The daughter was buried to the east of the church, while the bones of mother and son were transferred to the churchyard from another burial place. It is impossible to tell where that was.

*DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) is the material that makes up chromosomes – a molecule which contains the genetic “blueprint“ for each organism.

Disease

The people of Hofstaðir suffered from various diseases. Buried in the churchyard was a woman who had died of myeloma at the age of about fifty. This is the only case of a malignant tumour found in ancient bones in Iceland, and one of only a handful of cases in the world.

Myeloma is a malignant cancer of the bone marrow, caused by proliferation of monoclonal plasma cells. It remains incurable today. The skeleton of the woman in the Hofstaðir churchyard bore widespread signs of the disease: in the skull, vertebrae, ribs, shoulder-blades, clavicles, pelvis and femurs.

At the time of her death the disease was at an advanced stage, and she had undoubtedly been ill for a long time – perhaps for decades. She must have been in great pain at the end of her life. Heavy accumulation of plaque on her teeth, including the bite surfaces of the molars, indicates that she was receiving liquid food as her life came to an end. She must almost certainly have been given something to ease her pain. The fact that the woman survived for such a long time with her severe illness indicates that she must have been in good health before she fell ill, and that she received a good diet and good care.

Signs of multiple myeloma are prominent on the skull of a woman who died from the disease and was excavated in the cemetery at Hofstaðir. © The Institute of Archaeology, Iceland.